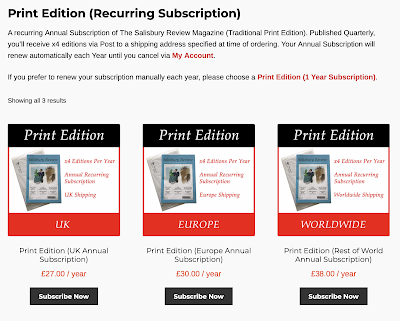

Here is my latest article for the Salisbury Review, which appears in the Autumn 2019 edition of this British magazine:

Since the Communists defeated the Nationalists in the 1946-49 Civil War, Australia’s approach to China can be divided into two very distinct phases. Firstly, there was naked fear of being overrun by the “red peril” and secondly, naked economic opportunism paired with the opposite of fear: geopolitical naivety. Right now, however, we appear to be at a crossroads. Are we heading back to an age of hostility, when relations were literally frozen, or towards a modus operandiin which we must kowtow to Emperor Xi Jinping’s reconfigured Middle Kingdom? Newspaper reports claiming that the United States is preparing to expend a quarter of a billion dollars on a new naval base in Darwin, Northern Territory, seem to suggest that in any emergent Sino-American stand-off our side has already been chosen for us, and yet there are Australians too invested in harmonious Sion-Australian relations to welcome any kind of Cold War-style confrontation in the Asia-Pacific region.

Australia, thinly-populated and a far-flung member of Western civilisation, has always been concerned about threats from the north, concerns that were confirmed by Imperial Japan’s astonishing military victories throughout 1942 – Hong Kong, the Philippines, Malaya, Borneo, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Not a few Australians were quietly fortified by the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor because it brought the United States into the Pacific War. Come the end of the Second World War, both Australia and New Zealand were keen to turn their wartime alliance into a peace-time military pact as protection against a resurgent Japan, a move Washington resisted. Not until Mao Zedong’s Communists took power in China in 1949, and subsequently played a key role in the Korean Civil War, did the Australian, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty (ANZUS) become a reality. ANZUS, during Cold War, was the Australasian counterpart to Europe’s NATO, except it was the People’s Republic of China (PRC), rather than the Soviet Union, that was to be the main focus of this anti-Communist alliance.

Remarkably, Canberra refused to recognise the legitimacy of the Communist-ruled PRC between 1949-72, maintaining diplomatic relations with the Nationalist Chinese who had fled to the island fortress of Taiwan after being routed on the mainland in 1949. I still remember, as a young and confused primary school lad in 1966, writing a letter to The Embassy of China for project material and receiving, by return mail, a large brown envelope with a map of Taiwan inside. My young British contemporary would never have received such a surprise, since Prime Minister Clement Atlee recognised the reality of the PRC as early as January 1950. Few Australians, or anyone outside of the PRC for that matter, knew much about what went on in Mao’s China, although general opinion was not favourable. It was, as we were to find out much later, a horror story beyond our darkest imagination, with 45 million dying during Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958-62). I was just old enough to start reflecting on the insanity of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and asked my father, while watching the television news one night, if the frenzied crowds waving about their Little Red Books were a danger to us. “They live a long way from here,” he assured me.

At some point, over the succeeding years, Australia’s official attitude to the PRC changed from negative estrangement to positive engagement. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, a towering man in stature and self-opinion, a scholar, lawyer, classicist and urbane in a way no Australian Labor Party Leader had ever been, gazed north towards our Asian neighbours, and specifically the PRC, and was able to assure his not-so visionary compatriots that they had nothing to fear but fear itself. His “historic visit” to China, and his tâte-a-tâte with Chairman Mao, preceded President Nixon’s “historic visit” by a year. On achieving office in December 1972, Prime Minister Whitlam shut down our diplomatic mission in Taipei and instigated a new era in Australia-PRC relations, one in which politicians, journalists, educators, diplomats, and – increasingly – businessmen – chose only to see good things in their “positive engagement” with Communist China. Every outrage implemented by the despotic regime in Beijing, the Democracy Wall crackdown in 1979, the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989, the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners since 1999, the brutal suppression of Tibetan protestors in 2008, the arrest of Ai Weiwei in 2011, the incarceration over a million Turkic Uighurs in Xinjiang, the harvesting of organs from prisoners for transplants, North Korean-style tactics against Christians, and so on ad infinitum, produces another call from our China apologists for more positive engagement.

The absolute personification of the China apologist would have to be Kevin Rudd, Labor prime minister from 2007-10 and then again briefly in 2013. Rudd, who learned to speak Mandarin during his earlier years as an Australian diplomat in Beijing, came into office as a China expert who understood how to work the PRC. The evidence, however, suggests Australia’s “positive engagement” with China, apart from a robust trade bonanza that saw us through the Great Financial Crisis virtually unscathed, became more fractious during Rudd’s tenure. Today Kevin Rudd is a scholar at Harvard University working on a biography of President-for-life Xi Jinping. He blames the recent downturn in China-Australia affairs on our politicians, such as former Coalition Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull (2015-18), for “being paranoid and all over the place” instead of establishing “systematic and comprehensive strategic relations”. More likely, it is the PRC’s Communist Politburo andthe hard-line President-for-life Xi Jinping, already in power at the time of Rudd’s second time as Australia’s prime minister, that has changed the rules of engagement. Take, for instance, China’s militarisation of the South China Sea, something Xi Jinping once promised would never happen. In 2017, when thethen Foreign Minister Julie Bishop challenged China’s about-face on the subject, a bitter diplomatic row immediately ensued. The PRC’s Communist Politburo decided that it would no longer tolerate Australia maligning the dignity of the Middle Kingdom, which – after all – accounted for almost 30 percent of our total exports or $110.4 billion during the period 2016-17.

The PRC’s sudden belligerence towards Australia, coming like a thunderstorm in the middle of summer, shocked many out of their complacency. Australia never officially signed up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in which Beijing invests billions into (say) Turkish infrastructure with the understanding that Turkey remains mute on the subject of China’s ruthless treatment of its ethnic cousins in Xinjiang. We never signed up to the imperialist-Leninist BRI, and yet hardly a week goes by without Beijing reminding Australians of the leverage it now has over us. Last year, for example, Communist China began demanding that Qantas remove any references in their businesses to Taiwan as a country. Australia’s Foreign Affairs chief, Frances Adamson, blasted China’s directive as “economic coercion”. White House spokesperson Sarah Huckabee Sanders was of a similar mind: “The United States strongly objects to China’s attempt to compel private firms to use specific language of a political nature in their publicly available content”. While American Airlines refused to submit to Beijing’s edict, Qantas quickly folded.

If Australia is not to end up as an associate member of Communist China’s version of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, it will be the United States, again, that saves the day. It was Candidate Trump who announced to a startled world that the era of so-called positive engagement with the PRC was over. The Communist Politburo had abused their membership of the World Trading Organisation (WTO) and, to use the words of Peter Navarro, author of Death by China(2012) and now the White House’s Office of Trade Manufacturing, it had been waging a war against America using the “weapons of jobs destruction”. Communist China, according to President Trump, is not necessarily an enemy of the West, but it is hardly a friend or even neutral factor in world relations. Moreover, the ruling class in Beijing has been intoxicated by a combustible mixture of economic power and political paranoia, as evidenced by their triumphalism abroad and unrelenting totalitarianism at home. Their comeuppance might occur if, and when, the Trump Administration manages to convince enough American corporations, through the judicious use of tariffs and other patriotic manoeuvres, to return manufacturing and production of every kind to the homeland.

But even if China’s BRI behemoth should be challenged or even thwarted, the military power and global ambition of the imperialist-Leninists in Beijing will – barring the overthrow of the regime – reverberate down through the years. Australia’s plan, as articulated by the recently re-elected Prime Minister Scott Morrison, is to play a vastly bigger economic role in the South Pacific in order to hinder Beijing’s BRI tentacles. And then there is the military and security angle, which explains the development of yet another military base in northern Australia. Today, significantly, it is no so much ANZUS but the Trilateral Security Dialogue (TSD) between the United States, Australia, and Japan that characterises our military alignment. A new kind of Cold War seems to be taking shape before our very eyes. Meanwhile, China apologists, such as Kevin Rudd and the academics subsidised by the PRC’s Confucian Institutes in universities around Australia, not to mention the multinational exporters of our mining resources and companies like Qantas and let us add property developers addicted to Chinese investment, will all be crying out for more “positive engagement”. We are, all of a sudden, living in what the Chinese traditionally call “interesting times”, a perilous, albeit historic, scenario not to be desired.

First appeared in Autumn 2019 edition of the Salisbury Review