Here is the piece I wrote for Autumn 2023 edition of the Salisbury Review

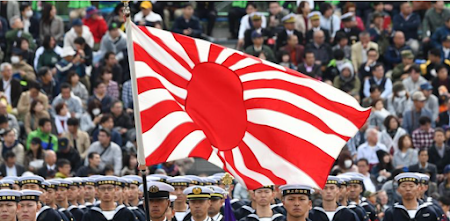

With the publication of Japan’s 2022 National Security Strategy, and the intention to increase defence spending to 2 per cent, there are now potentially not one but two military powerhouses in East Asia. While China’s PLA has experienced a dramatic build-up in the era of Xi Jinping, on the back of soaring defence budgets, the potency of Japan’s Self-Defence Forces is now on a steep upwards trajectory. Rishi Sunak has referred to the AUKUS agreement between the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia as ‘the most significant defence partnership in generations’. And that leaves out the fact that AUKUS is already, in all but name, JAUKUS – potentially the most powerful military alliance in history.

Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ (or Leninist-imperialism) is, from the perspective of Tokyo, an existentialist threat to the sovereignty of Japan. Chairman Xi, in 2013, established his self-styled East China Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) to enforce air control restrictions in the East China Sea, including the air space attendant to Japan’s Senkaku Islands. In 2015, as a direct response to Xi’s ADIZ, PM Shinzo Abe announced a re-interpretation of Article 9 of Japan’s 1947 ‘pacificist constitution’. Japan’s parliament (Diet) asserted the right to counterattack any foreign power – Russia, North Korea (which had started firing ballistic missiles over Japan in 1998) or China – that threatened the security of the homeland. Everything in the discussion that follows, then, is a consequence of Emperor Xi’s hubris.

But what, exactly, has motivated Japan to embrace Australia as its best friend in the Asia-Pacific region? The answer is not only the disputed Senkaku Islands lying between Kyushu and northern Taiwan, but the fate of Taiwan itself. It can be argued and has been argued by Prime Minister Kishida Fumio (Shinzo Abe’s successor), that the security of Japan and the security of Taiwan are inseparable. If Taiwan were to be annexed by the PRC, Japan’s southernmost territory is going to be almost impossible to defend. Additionally, the PLA Navy would not only threaten Japan from the west but also from the east. Japan would be reduced to its pre-Meiji status as a tributary state of the Middle Kingdom. No wonder Kishida has pledged to massively increase military spending over the coming years. Concomitantly, Australia’s membership of AUKUS, and the promise of eight nuclear-powered submarines (SSN-AUKUS) along with advanced capabilities in cyber, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies and undersea capabilities, doubtless explains why Japan’s eagerness to embrace Australia as its best friend in the Indo-Pacific region.

But why, you might ask, is Australia is so keen to embrace Japan? After all, in the Second World War Australia fought the Japanese on the Kokoda Track, at Milne Bay and in the Battle of the Coral Sea to prevent Imperial Japan capturing Port Moresby. Taking the capital of New Guinea, in the opinion of most of our historians, would not have led to the invasion of Australia, and yet it might have resulted in our (grudging) assent to membership of Imperial Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere (GEACS). Japan, after its defeat in the Pacific War, became a manufacturing and exporting dynamo. My late father, who fought against the Japanese as a Royal Australian Navy radio operator on the HMAS Wang Pu, a ship leased, ironically enough, from China, would sometimes wonder out loud about who, exactly, had won the Second World War. My uncle by marriage and his twin brother, as another case in point, were captured by the Japanese in the Dutch East Indies in 1942 and forced to work on Emperor Hirohito’s notorious Thai-Burma Railway, not inaccurately dubbed the ‘Death Railway’.

The attitude of Australians to Japan in the post-war era was, admittedly, complicated. Japan’s version of West Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder was in some ways irksome and yet Australia profited from the phenomenon. Our iron ore, coal, natural gas, minerals, seafood, beef, wool, timber, sugar cane and dairy exports all befitted from Japan’s economic miracle. If Imperial Japan had won the Pacific War, doubtless we would exported the very same goods to the resource-poor nation that is Japan. The difference, of course, is we would have transferred them to Japan as a more or less vassal state of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. As it was, Australia – as an independent, sovereign nation – sold these mostly primary at the market price, which in turn underpinned our own post-war economic miracle. The demise of Imperial Japan and the emergence of Democratic Japan, then, was not in vain. Moreover, Australia, as a Commonwealth occupying power in post-war Hiroshima prefecture, ensured that Japan’s new constitution was a liberal-democratic as possible, guaranteeing, for instance, female suffrage and independent trade unionism. Over time, furthermore, the people of Australia and Japan decided they liked each other. For instance, today Australians make up the plurality of the foreign skiers in Japan’s January snowfields, while Queensland’s Gold Coast has become the top overseas destination for Japanese tourists. We even drive our cars on the same side of the road.

Our half-century love affair with the People’s Republic of China is a different narrative altogether. President Xi’s declaration of war on our economy in 2020, after Canberra called for an international inquiry into the origins of COV-19, changed everything. It belatedly occurred to Australians that we had ensnared ourselves in Beijing’s version of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Australians were stunned when Xi – who previously spoke of a ‘regional strategic partnership’ with Canberra in our Parliament – instructed his English-language mouthpiece, the Global Times, to warn us that we would be taking ‘a walk into the darkness’ if we did not immediately cease all criticism of the People’s Republic of China. A year later, in its infamous Fourteen Grievances, Beijing demanded that Canberra forbid our independent media from reporting any ‘unfriendly and antagonistic’ articles about the Chinese government. The term ‘kowtow’ did not originate in China without reason.

It was at this historical moment, with the benefit of hindsight, that Australia’s relationship with Japan went into overdrive. In truth, Australia and Japan, as discrete military partners of the United States, had been de facto allies since 1951, the year that saw the signing of Japan-U.S. Security Treaty and the Australian, New Zealand and U.S. Security Treaty (ANZUS). Throughout the Cold War, Australian spy agencies were given the mission by Washington to monitor the western perimeter of the South Pacific, while Japan was tasked with scrutinising via aerial reconnaissance the western perimeters of the North Pacific. Thus, since 1951 Tokyo and Canberra have been, in practice, military partners even if this was not something about which most Australians and Japanese were cognisant. That said, the signing of the 2022 Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) between Canberra and Tokyo, allowing for the seamless interoperability of Japan’s and Australia’s armed forces in military and humanitarian missions, took things to a whole new level.

Today, as a consequence, the security alliance between Australia and Japan is as formal as our accord with America. This historical development had little influence on the 2022 national election, which saw the conservative Coalition parties defeated by the progressive Labor Party. Nevertheless, the new Labor government has unreservedly endorsed the RAA – only old-time China apologists, such as former Labor prime ministers Paul Keating and Kevin Rudd, oppose stronger military bonds between Australia and Japan. We might note, at this point, that on January 11 Tokyo and Westminster signed their own Reciprocal Access Agreement. Additionally, Japan and the UK (in partnership with Italy) are now collaborating on a fifth-generation fighter jet to be known as the Tempest. For modern-day Japan, as distinct from post-war-Japan, national security means not only national security but global security.

Kishida’s Japan is now at the heart of everything. As the host of the January 2023 Hiroshima G-7 Summit, it gave Ukraine’s President Zelensky a pulpit. At the July 2023 NATO Summit, Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg recognised Japan as the North Atlantic alliance’s closest partner. Japan has also been the driving force behind the Japan-India-US-Australia Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. Even more surprisingly, perhaps, PM Fumio Kishida (in in collaboration with South Korea’s President Yun Suk Yeol) has begun a process of thawing Japan-South Korea relations. Who knows, in time AUKUS may become JAUKKUS. We might fairly say, at this point, that Xi Jinping has – to paraphrase Napoleon’s adage – awakened a sleeping giant.